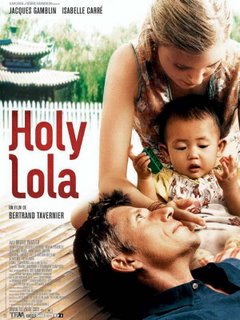

Angelina Jolie started it. Or was it Calista Flockhart? John Sayles’ just made a movie about it (Casa de Los Babys). Let’s face it: adoption is the es through close humanitarian introspection unquenched. Tavernier is famous for his detailed exploration of human interrelationships and social concerns. His most famous film is probably Le Juge et l’Assassin which focused on the relationship between a convicted child killer and the judge who must decide his fate. Tavernier is less concerned with plot and more concerned with his characters and the broader social or political commentary of his films. In 1977’s Des Enfants Gatés, Tavernier examined familial rapports and exposed urban malice. He journeyed to his native Lyon to explore the subject of family relationships in 1980’s Une Semaine de Vacances and in 1984 returned to a bucolic setting to highlight the relationship between an aging painter and his children and grandchildren in Un Dimanche à la Campagne. Tavenier’s films are simple yet powerful. He has made myriad films about war, including 1989’s famous La Vie et Rien d’Autre which starred Philippe Noiret as a World War I major obsessed with making amends for his participation in the violence of the war; 1992’s La Guerre Sans Nom, a documentary about the Algerian War; 1996’s Captaine Conan, a post-World War I drama about a captain and his troops in Bulgaria ;and, more recently, 2002’s Laissez-Passer, a three-hour drama taking place in France during World War II following two filmmakers and the decisions they make as they struggle for survival under German occupation. In Tavernier’s most recent film, Holy Lola, he again returns to international social commentary and an intricate analysis of the relationship between a couple, Pierre and Geraldine, (played by Isabelle Carré and Jacques Gamblin) struggling to adopt a child in Cambodia. Though Tavernier gives the spectator almost no background information about the couple, he invites the spectator into the lives of these strangers to experience all of the adventure, the administrative frustration, the disappointment and the joy of the complicated procedure of bringing a child into France. The film focuses on Pierre and Geraldine, but also shows other French couples staying at the same Phnom Penh hotel in various stages of the adoption ordeal. Tavernier asks the spectator to sympathize with his characters as they witness the corruption of bribery, poverty and exploitation of the adoption process and, at the same time, exposes the violence and harsh realities of life in contemporary Cambodia. The film is aesthetically successful – a visual masterpiece manifesting the sober reality of Cambodian life – yet failed to truly establish sympathy between the spectator and its main characters. I felt that I didn’t know Pierre and Geraldine well enough to truly care what happened to them; they, like the other couples in the film, desperately wanted a child – but why? And what led them to journey to Cambodia? In classic Tavernier style, Holy Lola has no discerned plot, only sporadic moments of chaos and adventure decorating a predominately banal landscape of biased character development and a clear effort to maintain a politically correct rhetoric. French critics have hailed the film as a masterpiece, “full of vitality and humanity” (STUDIO Magazine) and “a strong and true work that goes right to the heart […] a magnificent portrait of a couple” (Le Parisien). And while it is extremely moving (I’ll admit, I cried), the leading actors give incredible performances, and although I have been such a fan of Tavernier’s work for quite some time, I hold to my claim of injustice on the part of character development. Perhaps I expected more from someone who has made what I consider to be some of the greatest films of all time.

Speaking of the greatest films of all time, I went to the Paris premiere of Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason (aka Bridget Jones: l’Age de raison) last night. It is definitely not one of them. I did expect the worst after reading the scathing reviews from American critics (I believe the title of the International Herald Tribune’s review was “Bridget Returns, Unfortunately”), and I was given just that. The second Bridget Jones flick is a prime example of Hollywood’s unrelenting insistence on following up international hits with big-budget, mediocre, over-the-top garbage starring famous actors and made only to please as wide of an audience as possible all to the tune of cheesy contemporary pop songs. Though the film does have some redeeming moments – perhaps French humor has affected me, but I found myself hysterically laughing as I watched the puerile slapstick comedy of Bridget’s skiing scene – it is, in general, an embarrassment to Hollywood fascism.

7/12/04. Weight: unknown (i.e., I still haven’t figured out how to convert pounds to kilograms); alcohol units: 2 (red wine at lunch); cigarettes: 0 (I think I can safely say that I am THE only person in this entire office building – no, wait, country – who does not smoke); calories: who counts calories? I’m in FRANCE, remember? Bridget Jones films seen in lifetime thus far: 2. Bridget Jones movies enjoyed in this lifetime: 1. Number of times Hugh grant turned his face 90° and flashed the same charming smile found in over 95% of British or American romantic comedies: 34. Jokes made in poor taste: 17. Number of times the “magic mushroom” joke was played out before it got old: 5. French people eating popcorn in a theater of around 200 seats: 3. Americans eating popcorn watching across the Atlantic in a theater of comparable size: 199. Sequels that will probably become a part of the Bridget Jones franchise before the producers realize everyone is sick of Bridget Jones: 3. Number of people like myself who will mimic Helen Fielding’s diary-like writing style in an effort to be humorous: thousands.

Mon Trésor

Keren Yedaya

« Un film troublant, bouleversant. Un trésor. »

-STUDIO Magazine

(« A troubling and film. A treasure. »)

Winner of the Camera d’Or among myriad other awards at 2004’s Cannes Film Festival, Mon Trésor is aptly titled. This treasure of a film tells the story of Or, a young Israeli girl who desperately tries to liberate her mother, Ruthie, from her life of prostitution yet becomes gradually pulled towards such decrepitude herself. The film is at the same time extremely difficult to watch based on its realistically heavy content yet also aesthetically pleasing as Yedaya’s camera follows its main characters through motionless long shots and offers the spectator different perspectives through a variety in camera angle. Or does everything possible to try to prevent her mother from being forced to sell her body to pay the rent or put food on the table. She finds her a job as a cleaning woman and, when she sees Ruthie relapsing into her old profession, physically halts her in her efforts.

Both lead actresses give incredible performances, especially the young Or who delivers a frighteningly realistic portrayal of a 17-year-old who, in an effort to lure her mother away from prostitution, is drawn closer and closer to such a life herself. The film is dark yet splattered with tiny moments of hope that, in the end, fail to triumph over the cruel veracity of poverty. The film is pointedly feminist in its approach and invites the spectator to sympathize with its women and hate the male-dominated society that forces them to sacrifice their bodies with such ease.

Narco

Gilles Lelouche and Tristan Aurouret

While it is possible to gain comprehension of the French language with a few night classes and a vocabulary tape, French humor is a different language entirely, and one difficult to translate across cultural barriers. I mean, think about it: they adore Jerry Lewis! The ubiquity of humor in French culture might surprise those who envision the stereotypical Frenchman who sports a beret, carries a croissant and hasn’t smiled in the past ten years. However, contrary to popular belief, comedy – or rather the French definition of comedy – plays a large part in French daily life. Since the days of the Salons, “l’esprit” (or “wit”) has been an obligatory quality to possess in order to succeed. Yet, like foie gras and escargot, French humor is an acquired taste. Typical French comedy is characterized by slapstick hilarity, subtle innuendo and “jeu de mots” (“plays on words” or “puns”).

On television, the “Guignols” mock contemporary international politics and culture via caricaturized puppets resembling important political figures and celebrities. At the movies, French audiences are exposed understatedly sharp dialogue and absurd scenarios in which their favourite stars run clumsily around a set resembling the cartoon characters of their youth.

Narco, the latest offering from the young dynamic director duo Gilles Lelouch and Tristan Aurouret, is an American movie in every sense of the term, yet is overshadowed by clear manifestations of “l’humour française.” This ostensibly unintelligent parody is actually a dark comedy: a mélange of depressive tragedy and slapstick jest. The film stars popular young actor and director Guillaume Canet as Gustave Klopp who suffers from narcolepsy and falls asleep all the time, especially at extremely inopportune – and thereby comic – moments. His medical condition causes problems for his professional life (how can he be expected to hold a job when he can’t stay awake?) and his love life (his wife Pam, played by the stunning Zabout Breitman, grows increasingly tiresome of his unemployment and inability to discipline their rebellious young son). While he sleeps, however, Gus’ imagination runs wild and he dreams about exotic voyages and vividly real adventures which he begins to illustrate through a series of comics-book drawings starring his invincible superhero, Klopp. However, Gus’ psychiatrist, Samuel Pupkin, tries to steal ownership of Gus’ incredible comics and, with the help of Gus’ wife and best friend Lenny Bar nearly succeeds. Canet, normally lithe and clean-shaven, is almost unrecognizable as his bearded, brawny, narcoleptic alter ego and provides a ridiculously believable performance as a man who must learn to take control of his own existence. Benoit Poolvarde steals the show with his hilarious portrayal of an aspiring Karate star and Jean-Claude Van Damme wannabe bordering on alcoholism and mental illness. Narco is made with all the ingredients of an American blockbuster – popular stars such as Canet and Poolvarde with a cameo by Jean-Claude Van Damme, a large budget, cliché and widespread publicity and marketing – yet remains classically French thanks to its witty innuendo and inescapably slapstick moments of comedy (read: every time Gus falls asleep while performing common quotidian tasks). While the film was darker than I expected, I thoroughly enjoyed this quasi-Hollywoodian contribution from some of French cinema’s youngest adventurers.

No comments:

Post a Comment